Effective Communication

Clarity is necessary, but often insufficient.

Few things incite frustration and despair in presenters more than the four words "...I don't get it" at the end of a presentation. Unhelpfully, the statement often misrepresents the feedback, incorrectly suggesting that the audience had tried but somehow lacks the faculties to understand.

Why do audiences fail to "get it", and why are attempts to provide further clarification, once those fated words are uttered, always futile? What the heck is narrative? For those of your who know your Minto SCQAs, why do communications with well-constructed narratives still, sometimes spectacularly fail to land?

Why do we communicate?

The obvious but incomplete answer might be: because we want to share information, be it a fact or a particular way of looking at something (perspective) that we believe to be of value to the audience. However, effective communication must be something more.

Me: "There's a good chance you're going to crash our car tomorrow!"

My Wife: "No I'm not!"

The above exchange may be factually correct, certainly important, and direct enough to have been interpreted without ambiguity. Made with the best of intentions, somehow the interaction is nevertheless heading towards confrontation.

Me: "Are you planning to drive to work tomorrow? It's raining and its going to be -5C tonight - so the roads will be icy. I'm worried about you. Even if you are ok, there's good chance you'll be held up in traffic."

My wife: "What do you suggest I do?"

Me: "Take the train - I checked just now and it's running ok."

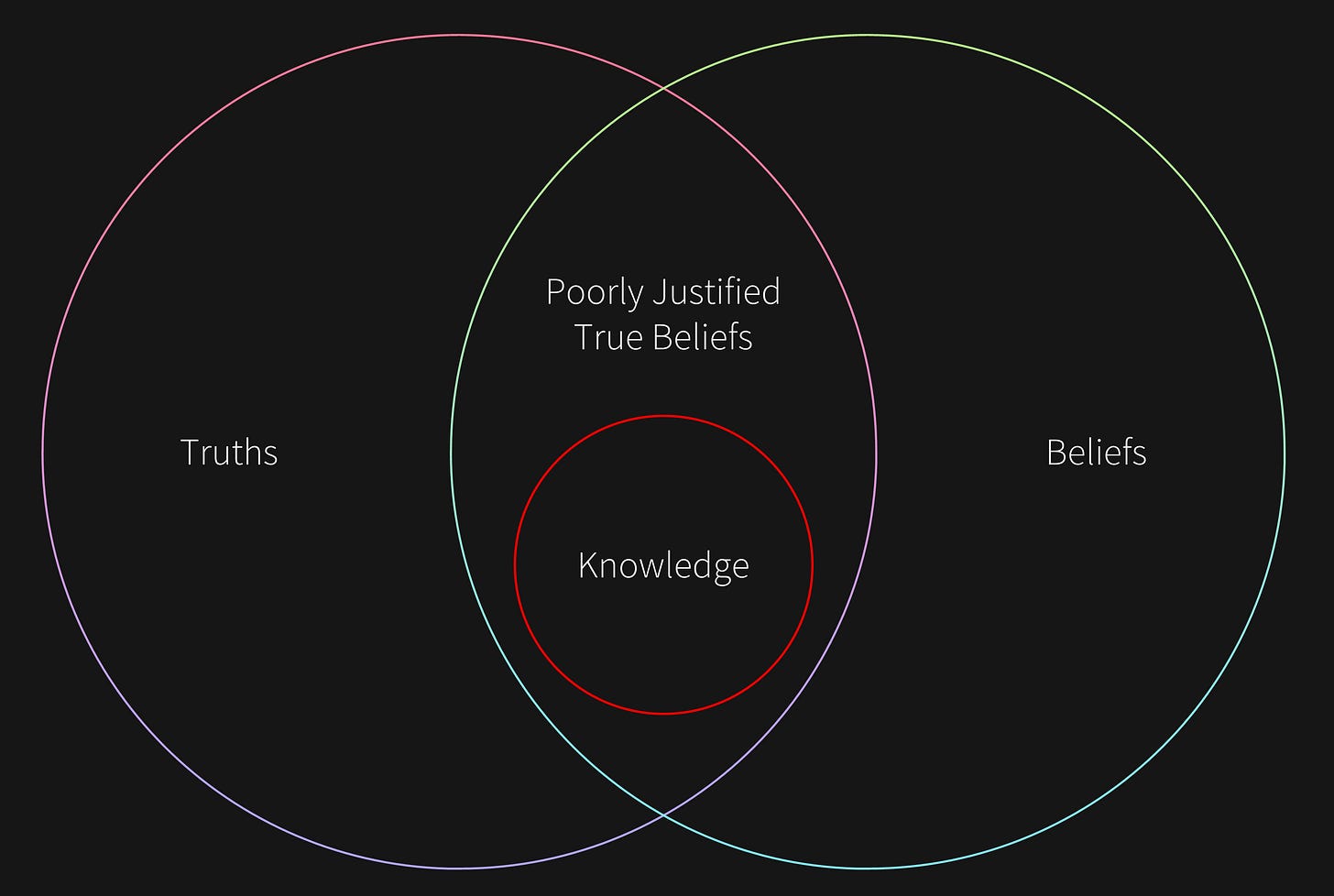

There is a difference between being provided truths ("Good chance of crashing tomorrow!"), and accepting truths as knowledge (affecting action). Consider this model of "knowledge" from philosophy:

Effective communications cannot just be about sharing of truths. For communication to have an effect, there must be an element of belief as well. Those dreaded words "...I don't get it" does not necessarily mean "I lack the faculties to understand your facts", but could also often mean "I don't see the significance of your what you are saying, therefore I am not going to invest in applying my faculties".

Effective communication, that is communications that has an effect, has two considerations: (a) structuring the communication to require the least effort to consume; and (b) establish belief.

Narrative devices

There is a lot out there on persuasion, ranging from traditional consulting literature centred on achieving clarity, to power games (yours truly chooses to avoid such games, but believe it wise to know the rules). Popular frames for constructing narratives include:

The Pyramid Principle1

On most professional service's reading list, containing examples of different narrative structures, e.g. situation, complication, question and answer (SQCA). In SCQA, Minto suggests starting by stating the situation (context), before stating the complication (necessitating the change from status quo), present the question (problem that has manifested as the result of the complication) before concluding with the answer.Toulmin Model2

A framework for argumentation that can be adapted for sense checking an idea. It can be difficult to see the bigger picture when we have been deep in thought; however, unless we do, we risk being blind-sided. What is the argument, how is it justified, and what might the pushback be?Rhetorical Triangle

Perhaps more art than a framework - Aristotle (384~322 BC) suggested that compelling speeches (rhetoric) can appeal to pathos (emotion and values), ethos (credibility) and logos (sound/cogent argument). What is your audience likely to be receptive to, and are you striking the right balance?

The above are just tools and having the best tools does not make a craftsperson.

...Why are they still not "getting it"?

Assuming that one is proficient in wielding the tools or at least reads and understands the manual, I have noticed three traps that technical presenters frequently fall into.

Writing for yourself, not your audience

All communication is two-way, including written materials such as reports and emails. It is not just "what you want to say", but equally also "what the audience is open to receiving". In every exchange, there are unspoken questions on both sides that need to be discovered and fulfilled. What does your audience want to get from the communication, what feedback do you want?Have confidence in the value that you bring. Resist the urge to "dive in and get there first".

Adding more detail, not context

Avoid always defaulting to logos - as someone with a technical background, when someone says "I don't get it", my immediate reaction is "more detail!" (thinking: "I can totally win this - my logic is flawless!").Keep in mind that your audience might not be a great (in this instance, precise) communicator. Are they really questioning your logic and asking for the next level of detail? What is it they are not voicing?

Failure to read the audience

Be mindful of what you are trying to communicate and the context in which it is received. The crack of dawn on Monday morning might not be the best time to suggest a risky endeavour, or maybe it is - you need to be able to accurately read the situation.Sometimes it is preferable to retreat gracefully than push on in the face of inevitable defeat. Rarely will you be provided with a second chance.

"Winning the argument" does not always equate to "winning people over". Knowledge is more than just facts - for something to be actionable, it must also be believed. Effective communication is not just about efficient sharing of facts through a well-constructed narrative, it must also entail establishing of beliefs as well.

Minto, Barbara. 2009. The Pyramid Principle: Logic in Writing and Thinking. 4th ed. Harlow, UK: Pearson.

Toulmin, Stephen E. 2003. The Uses of Argument. 2nd ed. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. https://play.google.com/books/reader?id=53whAwAAQBAJ.