Motivation × Risk

For change, acceptance of risks is equally important to having a compelling motivation.

Change entails risk. Enacting change requires more than compelling motivation, it needs those who are involved to be comfortable with the risks; to be in agreement that the outcome is necessary, and no easier/safer route exists.

When it comes to mobilising change, a clear and compelling vision is inadequate.

Imagine that you are on “Who Wants to Be a Millionaire?”. You have just expended your last lifeline getting to the 10th question, and are left with two possible answers on the screen. Answering correctly means going home with £500k, answering incorrectly will mean going home with the “safety-net” winning of £50k.

With no idea of what the right answer is, do you:

“Bank!” and go home with a guaranteed £250k, or

Hope to double your winnings by picking an answer at random?

By a long shot, option (1) is the popular answer amongst my friends and family. The possibility of going home with £50k, rather than the £250k is just too painful - after all, a bird in hand is worth two in the bush.

Option (1) is actually the “wrong” (non-optimal) choice. Having reached the safety-net, we are guaranteed to be £50k richer, so the actual value of the choice is for:

100% × £200k = £200k

50% of picking the right answer × £450k = £225k

In spite of the irrefutable logic above, I would still be reluctant to pick option (2). This is the same reluctance that stakeholders feel when faced with a transformational proposition, even ones with clear benefits. The reluctance is not about further “clarifying the vision” - i.e. option (2) is better by precisely £25k. So what is the reluctance really about?

Motivation

Much of the literature on the topic of change focus on articulating and championing motivation, be it by creating urgency1, painting the big opportunity2 or through a greater, unifying purpose such as a strategic intent3. Despite this established wisdom, too many initiatives still seem to rush to solutioning and implementation before establishing clear motivation.

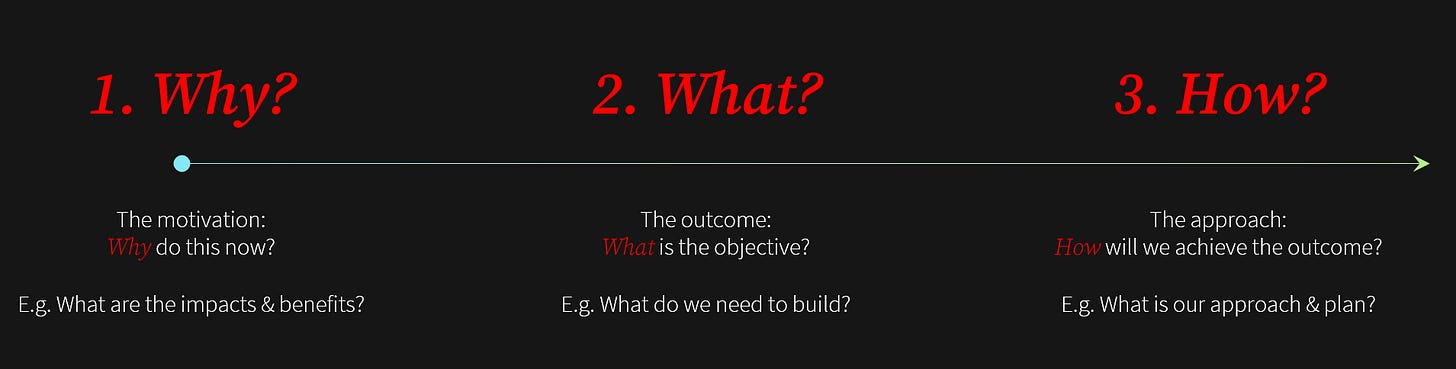

All too often, the motivation (why change?), objective (what are we building?) and approach (how are we going to build it?) are fatally conflated. Think back to the transformation programmes you have been involved in, for how many could you confidently describe the objective and approach? What about the purpose/reason for urgent change?

Change requires commitment across the organisation; however, not everyone will understand the importance of master data management or integrated sales and operations (both are examples of objectives), and that is ok. Stakeholders can understand how change can affect the business - the impacts/benefits of being able to trust reports so critical decisions can be made with confidence, and matching demand with supply to mitigate overstocking/stockouts (example of motivations).

Motivation comes down to distilling the irrefutable statement that necessitates change. For those who are doing the change, this distillation can be surprisingly elusive. The distinction of composition versus aggregation (in the context of UML modelling) is just as foreign to a business sponsor as is that of core competence (in the context of strategic architecture) for a technical architect. Yet, it is often up to the programme team to justify the motivation.

Even though irrefutable motivation is absolutely necessary, it is still only one side of the coin in mobilising change.

Risk

The harsh reality is: change entails risk - if there is no appetite for risk, there cannot be change. However, it is often possible to quantify and materially reduce the risk. A good thing too - unless stakeholders are comfortable with the proposal, they cannot be committed to the gamble.

Think back again to the transformational programmes you have been involved with. What proportion of time was spent on clarifying the vision and designing the solution, versus time on figuring out ways to minimise risk and disruption?

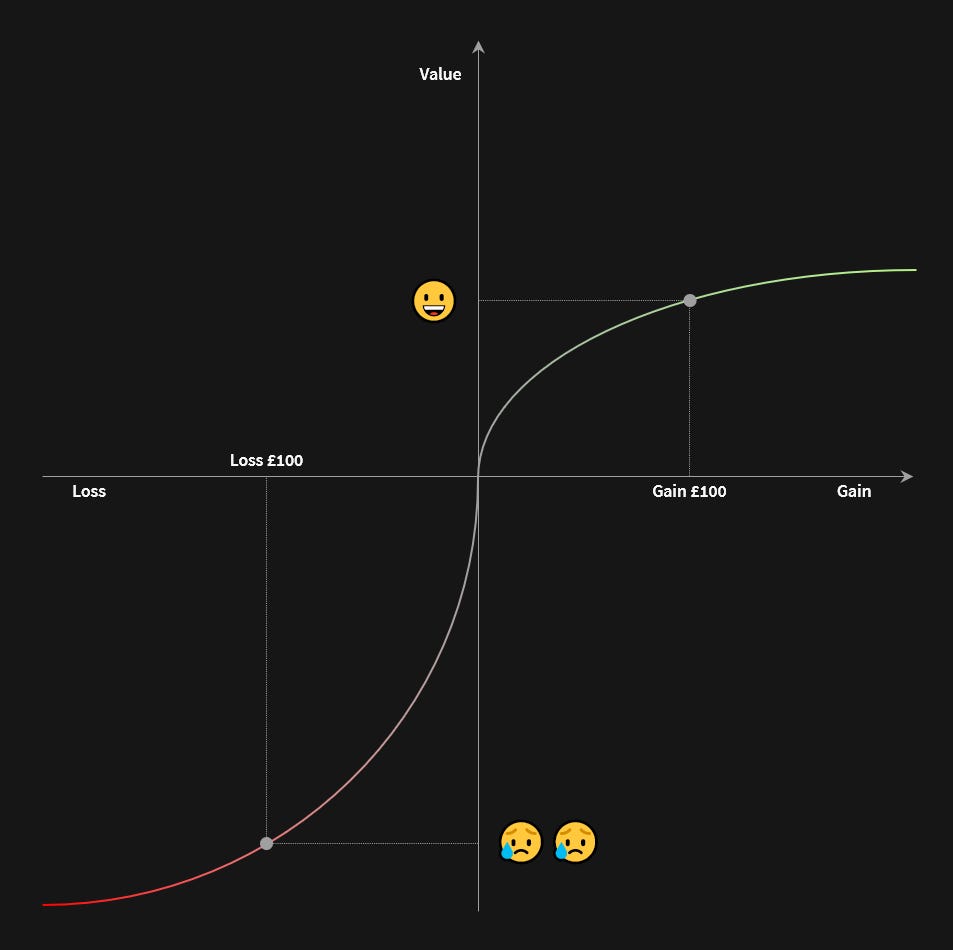

The reality is that people, in general, are loss-averse. The reluctance illustrated in the opening “Who Wants to Be a Millionaire?” example shows that the “correct” (optimal) answer is not always the most comfortable one. Prospect Theory offers a precise formulation4:

Losses are perceived to be much more painful than the equivalent gain. In the “Who Wants to Be a Millionaire?”, avoiding the possibility of loss is worth at least £25k.

Humans are generally bad at evaluating very low and very high probabilities - e.g. that we tend to equate 1% and 5%; and similarly 95% and 99%.

PT is a model, and cannot be expected to describe every interaction. The purpose is to illustrate that a risk mitigated is possibly, perhaps even often, worth more than the equivalent benefit gained. Despite this, current doctrine places disproportionate focus on the potential benefits.

Framing

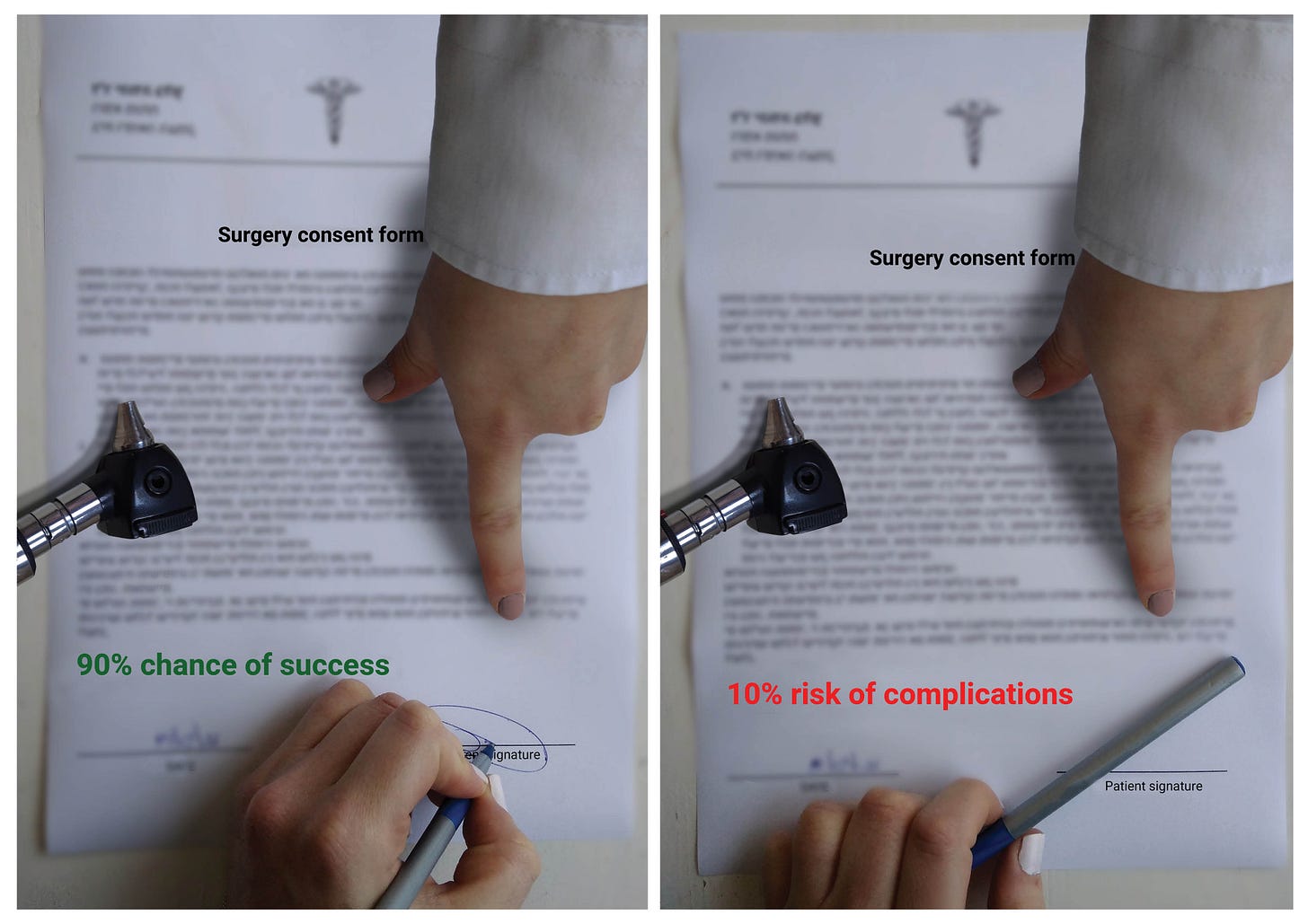

Accepting that (in general) we value losses more than gains opens up the question of framing5 - that how we describe a gamble could influence the choice.

An intuitive example from Wikipedia6 - which do you find more compelling?

Change is more likely to succeed when stakeholders are committed, not just compliant. Commitment comes from the confidence of arriving at a conclusion objectively - having fully understood the pertinent available information.

Those who bear the risk must be truly comfortable with the gamble, not persuaded or argued into submission.

Three questions

Here are three questions that test the foundations for change.

Is the motivation clear?

Motivation is the reason that necessitates change and justifies the risk.

Motivation is different from objective and approach. Avoid the trap of believing that what and how can be replacements for compelling why.Are stakeholders convinced that no safer routes exist?

Risk cannot be an afterthought.

Unless convincing mitigation is part of your proposal, you may find it difficult to get the initiative going; or worse still: doom the initiative by mobilising without the right stakeholders on board.Are you persuading, or informing?

Motivations and risks should not be biased towards a particular frame. Inform by providing multiple frames to help stakeholders see the wider picture.

Picking a frame for the purpose of influencing a particular outcome could result in fickle commitment.

For change to happen, those who bear the risks must be genuinely comfortable with the gamble. Comfort comes from an informed conclusion that the risk is both minimised and necessary.

Kotter, John P. 2012. Leading Change. 2nd ed. Boston, MA, USA: Harvard Business Review Press. https://play.google.com/books/reader?id=8jjZc6OX3O0C.

Kotter, John P. 2014. Accelerate. 1st ed. Boston, MA, USA: Harvard Business Review Press. https://play.google.com/books/reader?id=RFzOAgAAQBAJ.

Hamel, Gary, and C. K. Prahalad. 1989. ‘Strategic Intent’. Harvard Business Review 1989 (May-June). https://hbr.org/2005/07/strategic-intent.

Kahneman, Daniel, and Amos Tversky. 1979. ‘Prospect Theory: An Analysis of Decision Under Risk’. Econometrica, Choices, Values, and Frames, 42 (2): 263–91.

Kahneman, Daniel, and Amos Tversky. 1984. ‘Choices, Values, and Frames’. American Psychologist, Choices, Values, and Frames, 39 (4): 341–50.

Brichta, Mushki. ‘Framing effect illustration’. Wikipedia. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Framing_effect_(psychology). CC BY-SA 4.0. No changes made.

Photo by Robert Ruggiero on Unsplash